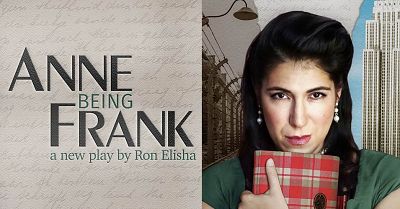

Anne Being Frank

Click here if you liked this article 56 ![]()

https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/theatre/anne-being-frank

Date Reviewed: 14/09/2025

What if Anne Frank had survived – and insisted on telling the whole story? This play dares to propose such a possibility. Written by Ron Elisha, an Israeli-born Australian playwright, who practised as a GP until his retirement in 2016, it re-imagines Anne not as a tragic symbol, but as a woman poised to reclaim her story by rewriting her infamous diaries as a published memoir. It’s a provocative premise that invites audiences to confront the tension between history and fantasy, trauma and recovery.

The production’s clever stage design enables deft movement across three distinct settings: the hidden annex in Amsterdam where Anne first recorded her thoughts; the imagined scenes of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, described with unsettling precision; and a 1950s New York publishing house, where Anne spars with an editor over how her story should be told. These transitions, while ambitious, occasionally disrupt the emotional continuity of Anne’s character, making it harder to reconcile her shifting states of being.

Alexis Fishman delivers a flawless solo performance, embodying Anne across these shifting contexts with impressive range. She captures Anne’s youthful defiance, intellectual curiosity, and later, imagined resilience. Fishman’s vocal work is especially compelling, and her singing offers moments of reprieve and sentiment. In Amsterdam, Anne sings for Shabbat with tender memory. In Bergen-Belsen, a midwife hums in remembrance of her daughter. These musical interludes are among the production’s most poignant offerings.

The script honours Anne’s precocious wit and literary passion. Her teenage frustrations are sharply drawn: “I had a normal life until Hitler barnstormed my life.” Her sensory imprint of war is as “a stench of German sausage,” which is both mundane and symbolic. Her love of books is a lifeline: “Books make me feel safe,” she confides, during “long painful silent days that are hard to fill.”

The imagined scenes at Bergen-Belsen are harrowing. Anne is portrayed as enduring unspeakable violence, described as “a young girl used as a woman,” and the fevered delirium of typhus is rendered as a death sentence. These moments are difficult to absorb—and rightly so. Yet at times, the narrative stretches credulity, interrupting our emotional connection with Anne. One such moment occurs when Anne offers a consoling embrace to the German soldier who has repeatedly assaulted and raped her. Her gesture of forgiveness, while perhaps intended as a symbol of transcendence, feels emotionally unearned and dramatically convenient. It risks undermining the gravity of her suffering and the psychological realism of survival.

In the New York scenes, Anne debates the tone of her memoir with an editor who prefers the innocence of her original diaries. Anne insists on being “frank” about Bergen-Belsen’s horrors, while her editor urges restraint, preferring the innocence of the original diaries. This tension raises important questions: Who gets to shape survivor stories? And for whom are they shaped?

The frequent shifts between three settings - Amsterdam, Bergen-Belsen, New York - sometimes dilute the coherence of Anne’s character. The confident Anne of New York sits uneasily beside the traumatised girl of Bergen-Belsen. What internal journey allowed her to survive the darkness and speak with such clarity? This remains unexplored, and its absence feels like a missed opportunity to explore the psychology of survival. Still, the play is a bold and moving experiment that releases Anne Frank into a future and invites us to imagine her as a resilient woman with more of her story to tell.

This production didn’t offer easy answers, but it did offer a kind of imaginative justice. It invited me to sit with discomfort, to listen more closely, and to consider how we carry the voices of others, especially those silenced too soon.

Reviewed by Sharon Stockwell